Where even to start? The backlash against Prime Minister Liz Truss and finance minister Kwasi Kwarteng’s unfunded fiscal plan – drafted by right-wing ultra-free-market policy think-tanks working at the heart of government – was global in nature, quick to emerge and ferocious.

The plan, intended to be financed by massive borrowing in a rapidly-rising rate environment, massacred any credibility the UK government had after investor support vaporized. The International Monetary Fund was patently hostility to the plan: “We do not recommend large and untargeted fiscal packages at this juncture as it is important that fiscal policy does not work at cross purposes to monetary policy. Furthermore, the nature of the UK measures will likely increase inequality.”

This preceded a warning from the Bank of England: “Were dysfunction in [the long-dated UK government debt] market to continue or worsen, there would be a material risk to UK financial stability.”

And then came the humiliating jibes about the UK behaving like an emerging market ( EM ). Ray Dalio, founder of Bridgewater Associates, has this to say on Twitter:

“Investors and policymakers: Heed the lesson of the UK's fiscal blunder. The panic selling you are now seeing that is leading to the plunge of UK bonds, currency and financial assets is due to the recognition that the big supply of debt that will have to be sold by the government is much too much for the demand. That makes people want to get out of the debt and currency. I can't understand how those who were behind this move didn't understand that. It suggests incompetence. Mechanistically, the UK government is operating like the government of an emerging country.”

Former US treasury secretary Larry Summers thinks the UK is “behaving a bit like an emerging market, turning itself into a submerging market. There’s nothing in the pattern of market response in the UK that suggests anything but fear, rather than confidence, in the policy approaches being taken … I think Britain will be remembered for having pursued the worst macroeconomic policies of any major country in a long time.”

Kenneth Clarke, a former UK Finance Minister, similarly took up the EM theme: “I don’t accept … the overall premise of the budget, which is that you make tax cuts for the wealthiest 5%, and it makes them work so much harder [so there’s a] rush to invest. I’m afraid that’s the kind of thing that’s usually tried in Latin American countries without success.”

The impacts of the fiscal plan could be catastrophic for ordinary UK citizens. Banks rapidly yanked mortgage products off the market in recent days just when homeowners face crippling rises in mortgage rates. These are the same people already being battered by raging food and energy inflation who – OK, will benefit from the government’s plan to cap energy bills – but won’t benefit from the planned tax cuts aimed at the wealthy and will net-net be significantly worse off.

There were no immediate signs that the government intends a rethink; in fact, it was more a case of doubling down. Calls from the Labour Party opposition to recall parliament to deal with the crisis received no immediate response. The same was the case for urgent calls to the government from bankers Kwarteng met during the week to bring forward the planned November 23rd date the government has set to make a fuller statement on its plans. That’s seen as way too distant.

Gilts are trading with a “moron risk premium”, says one observer of events. “I’ve never seen such raging incompetence,” says another. And the humiliation kept on coming: “inept madness”, says one MP. The government’s mini-budget was described by others as: “reckless”; “it was policy incoherence personified”; reflecting “the government’s culpable failure to acknowledge constraints on public borrowing resulted in political humiliation”; “an extinction-level event for the Conservative Party”; and illustrating “an enormous distance between rational reality and this government”.

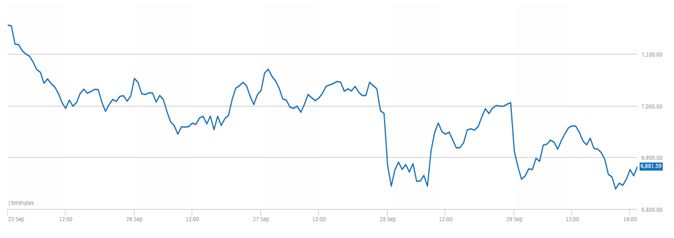

The spectacle of the UK Treasury and the Bank of England ( BoE ) working directly against one another as everyone stood by open-mouthed as gilts and sterling crashed while talk emerged of an emergency BoE meeting to jack up rates was pretty shocking. Some investment banks are forecasting that sterling will break parity with the dollar in short order and trade through by year-end.

The near collapse of heavily derivatives-dependent liability-driven investment ( LDI ) strategies that lie behind defined benefit UK pension schemes was chilling. Institutional investment firms running LDI strategies – worth £1.6 trillion ( US$1.75 trillion ) – running out of cash, bonds and other assets to sell to meet collateral margin calls on interest rate swaps as long-dated gilts entered a death spiral crash was eerily reminiscent of the global financial crisis ( GFC ).

And just as the inter-connectedness of massively leveraged firms in the wholesale financial markets jammed markets shut back in 2007-2008, here again we had the spooky re-appearance of heavily leveraged derivatives counterparties in a near-fatal make-or-break scenario. The BoE’s rapidly assembled £65 billion asset purchase facility to stabilize long gilts and rescue LDI shops only served to strengthen the parallels with the GFC. In creating inflationary impulses, the asset purchase facility has forced the bank to push back against its own inflation-busting mission. Quantitative tightening turned overnight into a re-run of quantitative easing.

With investment banks acting as the principal derivatives counterparties to LDI shops, let’s see if we glean any insights ahead of or during the forthcoming Q3 reporting season about who was in hock to whom for how much.

GBP/USD

.jpg)

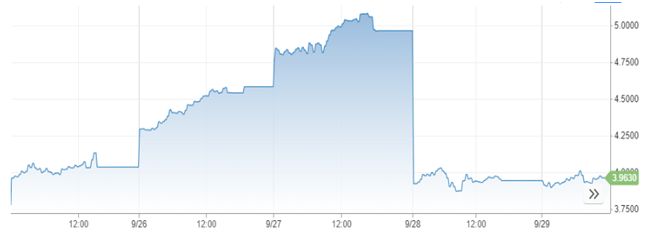

30-year UK gilt yield

FTSE 100